It is at this time of the year, as Samhain approaches, the spirits of the dead were (and indeed are in some cases) welcomed into homes and many people turn their thoughts to the macabre. But not me. I’m preoccupied with misery year-round. For more than a decade I’ve been researching and writing about murder, punishment and incarceration. I’m currently writing a book about the Irish obsession with suffering and death – a book which has grown out of my research on dark tourism.

In 1996 John Lennon & Malcolm Foley defined dark tourism as ‘the phenomenon which encompasses the presentation and consumption (by visitors) of real and commodified death and disaster sites’. Essentially, it’s tourism closely associated with death, suffering and the macabre, and Ireland, with its myriad of sites associated with incarceration, emigration and famine has plenty of that on offer for visitors.

Early studies of dark tourism tended to focus on sites associated with the holocaust – particularly concentration camps. But this is a rapidly expanding field of research and in recent years academics have written about prison islands such as Alcatraz and Robben Island. Considerable attention has also been paid to Ground Zero in New York and the Peace Memorial Museum in Hiroshima amongst others. However, few historians have engaged with dark tourism and very little has been written about dark tourism in Ireland. That’s not because there isn’t any, far from it. When I began to research dark tourism I drew up a list of half a dozen sites, but as I travelled around the country I began to discover many more. Currently there are over seventy sites on my list, scattered through almost every county in Ireland. In some ways this is no surprise. From birth the Irish are buried alive in a never-ending avalanche of stories, ballads, plays, wakes, dirges, poems, paintings, ceremonies, museums and heritage sites that celebrate the macabre. From the tribulations of Peig Sayers to the plays of Samuel Beckett, we are reared on tales of suffering, oppression, misery, failed rebellions, famine, civil wars and emigration. As I toured the country examining how museums and heritage sites narrate Ireland’s difficult and often tragic past I am also looking at the landscape of loss and how the countryside bears the scars of much of the county’s dark history.

Academic study of dark tourism may be a relatively new phenomenon but people have been visiting sites associated with death, suffering, incarceration and execution for their entertainment for centuries. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries public executions were often regarded as popular entertainment while Dartmoor Prison has been attracting curious visitors since the late-nineteenth-century, so much so that in the 1930s the voyeurs gathered outside the walls were banned from taking photographs of the prisoners. In Ireland, people have been visiting the vaults in St Michan’s Church in Dublin to take a look at the mummified bodies since the early nineteenth century. This sort of tourism has always been controversial. In 1847, at the height of the famine, Alexis Soyer (a chef at the Reform Club in London) set up a ‘model’ soup kitchen in Dublin. Up to 5,000 people were fed a day, but the kitchen was also a spectacle and the elite of Dublin could pay to watch. The Freeman’s Journal was outraged and compared it to paying to watch feeding time at the Zoo.

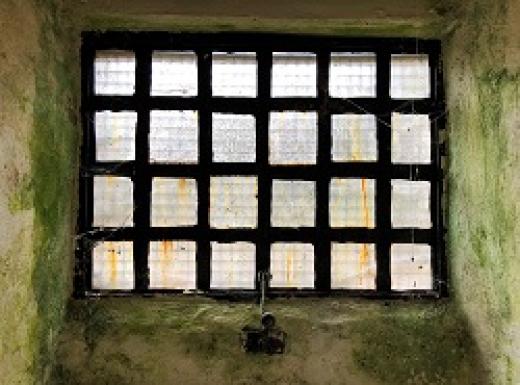

Philip Stone has identified shades of dark tourism: the darkest are sites of death and suffering focused primarily on education and historic interpretation, while the lightest are sites with a greater focus on entertainment. Different sites attract different types of visitor. Some sites, particularly concentration camps, are similar in ways to sites of pilgrimage where visitors go to pay their respects to the millions who died in the holocaust. Some go to try and make sense of it, some to pay homage to those who died, and some go so they can say that they’ve been. Other locations are popular largely because many people are curious about the past and have a particular fascination with stories associated with crime and punishment. Some may visit these sites for the same reason that people like horror books or films – to step into another, less palatable world, but to do so without risk. The buildings that house dark tourism exhibitions are often key to attracting the visitor, particularly when sites such as forts, prisons and workhouses were previously inaccessible to the public.

Whatever the motivations are for visiting it’s clear that across the world, sites associated with death, suffering and disaster are attracting increasing numbers of visitors. Each year over two million people visit Auschwitz-Birkenau, over 300,000 make the trip to Robben Island and about 1.3 million visitors step off the ferry onto Alcatraz. In Ireland over 400,000 visit Kilmainham Gaol annually. Yet, dark tourism doesn’t officially exist as a ‘thing’ in Ireland. You won’t find Fáilte Ireland advertising ‘Ireland in the Shadows’ alongside the Wild Atlantic Way or Ireland’s Ancient East. But of course dark tourism does exist – so many of our museums and heritage sites deal with ‘difficult heritage’ and a very complex past. There are all sorts of sites that could be labelled dark tourism – not just the obvious ones like Wicklow Gaol and Spike Island. The country abounds with workhouses, cemeteries, battle sites and forts and there is darkness in unexpected places. At the Rock of Cashel visitors learn about the ecclesiastical site, but also hear stories about a massacre of 600 people that took place there in 1642. One of the most striking dark tourism developments is the Kilkenny Famine Experience where, armed with an audio guide, the visitor is led around the former workhouse which now makes up part of the McDonough Junction shopping centre. There is something very surreal about standing in the middle of a bustling food court listening to tales of misery and starvation.

Some dark tourism sites are far more commericialised than others. To a large extent how commercial a site is depends on how it is funded. In some cases, it’s absolutely vital that a site generates sufficient income to remain open. Tourism is a business and commercial realities are a factor in developing any tourist site. With Halloween just around the corner, several prison sites in Ireland have Halloween-themed events. Crumlin Road Gaol in Belfast has a paranormal ghost hunt and ‘Jail of Horrors’, a ‘gruesome scare attraction’, while Wicklow Gaol encourages adult visitors to ‘take an eerie night tour of Wicklow Gaol – Ireland’s most haunted building’. Spike Island offers night tours which tell ‘a sombre and frightening history about prison life that is not for the faint of heart’.

Ghoulish interest might lure many tourists to sites, but most sites make significant efforts to contextualise their history. While some websites may emphasise gruesome executions, daring escapes and famous prisoners, passengers or inmates, in most cases visitors to the sites get a much more nuanced experience.

Most dark tourism sites in Ireland – such as prisons, workhouses and forts – are site-specific. Stories are told in the places where tragic and upsetting events have occurred. These sites possess something that no purpose-built museum can offer – authenticity. One of the great challenges facing those developing and running dark tourism sites is how to maintain authenticity and integrity while also telling complex (and often upsetting) stories in a compelling and attractive way. A fine line needs to be walked between education, entertainment and sensation and for the most part the dark tourism sites in Ireland do just that.