“I’m Pierrot, I’m Everyman. What I’m doing is Theatre and only Theatre...What you see on stage isn’t sinister, it’s pure clown. I’m using my face as a canvas and trying to paint the truth of our time on it. The white face, the baggy pants – they’re Pierrot, the eternal clown putting over the great sadness…” – David Bowie (1976)

One year on, and as people continue to process the death of David Bowie, who was quietly and unceremoniously cremated – ‘ashes to ashes’ – tributes continue to flow, and fans and critics alike rehash old interpretations of his vast back catalogue and offer fresh insight into his last creative offerings – the album Blackstar; Lazarus, the musical and the EP ‘No Plan’ – trying to make sense of it all. As local evidence of this, there was a footfall of some 10,000 people at the January 2017 Dublin David Bowie Festival, where his music and his art were closely dissected by fans and critics alike over five days.

Throughout 2016, the image of Starman loomed large – in media discourses about Bowie and especially in the title track of his final album release which continues to undergo extensive, post-mortem examination. Earlier this month, BBC Two’s David Bowie: The Last Five Years recreated the making of the last two Bowie albums with the view to understanding the degree to which he was consciously encoding messages about his own mortality and imminent demise.

Bowie’s death, unexpected by his fans, has resulted, of course, in an even closer scrutiny than usual of his complex multi-layered creative outputs. In spite of the many challenges presented by his failing health, Bowie managed to record two videos to accompany his ‘Blackstar’ album. As parting gifts to his fans, the videos for the songs ‘Lazarus’ and ‘Blackstar’ are encoded with a multitude of possible meanings. In ‘Blackstar’ the figure of the spaceman referencing Major Tom in ‘Space Oddity’ and ‘Ashes to Ashes’ has been transformed into a jewel-encrusted skeleton. In the ‘Lazarus’ video Bowie wears a striped outfit, which recalls one he had worn previously on the back cover of his album ‘Station to Station.’ In both videos his eyes are bandaged implying imminent execution. The presence of buttons over the eyes signifies, perhaps, the ancient Greek tradition of placing coins on the eyes of the dead in order to pay Charon the ferryman of Hades to carry them over from the land of the living.

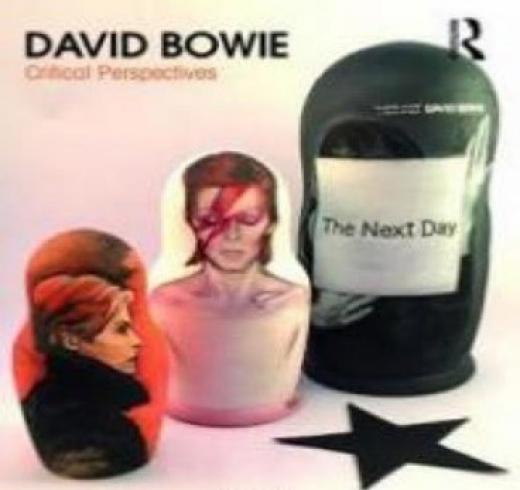

While aliens in various guises, and starmen in particular, are central motifs associated with Bowie, less attention, perhaps, has been paid to another avatar from the Bowie’s personae arsenal, namely that of Pierrot the sad clown. While Major Tom/Starman are untethered (although Chris Hadfield added a new dimension with his 2013 recording of ‘Space Oddity’ quite literally from space), it is Pierrot – who similarly appears and re-appears in Bowie’s oeuvre as a figure of continuity in key moments of his long career – that is replete with historical significance. Indeed, as we note in the latest edition of our book David Bowie: Critical Perspectives (2017), Pierrot the sad and sometimes insolent clown is a recurring figure in David Bowie’s oeuvre. His first flirtation with Pierrot came in the 1967 production of Pierrot in Turquoise, a theatre creation of British choreographer, actor, and mime artist Lindsay Kemp. Bowie didn’t play Pierrot (he did sing the song ‘Three-Penny Pierrot’) but was hugely influenced by this experience. ‘Ashes to Ashes’ (1980) was the first full rendering of the clown in the suitably titled Scary Monsters and Super Creeps album (is there anything more ominous than a clown?). All three of the record sleeves used to promote the song featured Bowie dressed as the clown.

Pierrot disappears for a while and then in 2013 Bowie dramatically resurrected a black Pierrot in his self-directed, homemade video for the single release of ‘Love Is Lost’ (2013) taken from the album The Next Day. Reportedly produced for just $12.99, the video featured mannequins from the David Bowie Archive, namely Pierrot and The Thin White Duke. Many readings could undoubtedly be made of this music video. The merging of Bowie and Pierrot; the resurrection of the sinister looking Thin White Duke; the frightened vulnerable clown dressed in funereal black; Pierrot’s feet tap-dancing in the expectation of a visit from Columbine; the skeletal shadows and the obsessive washing of hands all suggest potentially fruitful starting points for analysis and discussion.

Clowns resurface on his final album Blackstar (2016). The ‘clown’ figure is referenced in the final lyric of ‘Sue’, and you could also make the argument that the button-eyed Bowie and bejewelled skull in ‘Blackstar’ and ‘Lazarus’ have more to do with Pierrot than with any other of his characters. Certainly, Pierrot as an ill-fated figure, as a puppet to the vagaries of life, fate and destiny, seems darkly apt.

So who is Pierrot and what did a funny, sad, even dated clown have to offer a pop star whose spaceman personae seemed to be so much more suited to the time? Quite a lot actually, when one looks at the persistence of this character across countries and centuries. Pierrot emerged from commedia dell’arte theatre in sixteenth-century Italy and spread across Europe and beyond. This genre was full of self-conscious theatricality, exaggeration, and artifice (sound familiar?) and Pierrot developed into a more a more complex figure, a beautiful if often lost soul, becoming a vehicle for some of the greatest works in the expressive arts, including theatre, painting and, of course, music.

The figure of Pierrot offered a way into the cabaretesque and the carnivalesque for Bowie. ‘Ashes to Ashes’ makes that clear, with its nursery rhymes and distorted world that owes more to early twentieth-century Expressionism than any other time (think of Edward Munch’s ‘The Scream’). David Bowie was quite familiar with German culture and politics during his time spent in Berlin (1977-79), which built upon his exposure to expressionist art in his early days as a student. It is highly possible he was influenced by the German composer, Arnold Schoenberg, who wrote the dramatic piece ‘Pierrot Lunaire’ (‘Pierrot of the Moon’) in 1912. A self-portrait by Bowie below would lead one to think he knew Schoenberg’s artwork too, given the striking similarities in form and style.

As the ‘David Bowie Is…’ exhibition demonstrated, as it travelled the world, Bowie was clever at drawing from great writers, philosophers, artists, and musicians and reassembling these materials for his own ends. So as an archetype and a dramatic convention, Pierrot was a perfect vehicle for tapping into these masters of their craft, further allowing Bowie to be written into that grand narrative of Artist and Art with capital As (possibly the first pop star to be viewed in this way?).

But Pierrot was also a less lofty figure, someone who everybody could potentially recognise and understand. This was a truth that crossed the entire span of Bowie’s career, so there must be something to it.

Aileen Dillane, Eoin Devereux, and Martin J. Power, University of Limerick.

David Bowie: Critical Perspectives (Dec 2016 Paperback): https://www.routledge.com/David-Bowie-Critical-Perspectives/Devereux-Dillane-Power/p/book/9781138631205