Credit: Wellcome Library, London

Printed text

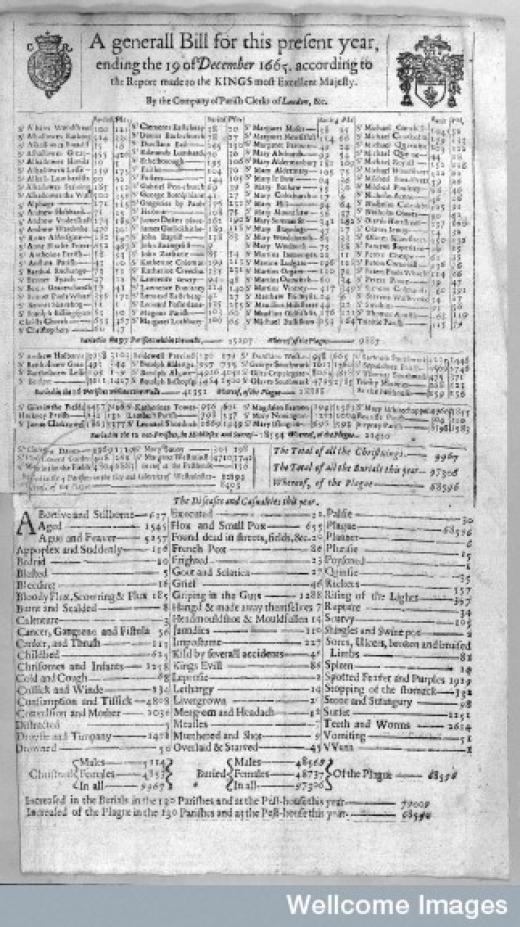

From: London's dreadful visitation: or, a collection of all the bills of mortality for this present year

Published: E. CotesLondon 1665

Folio 05 recto

Collection: Rare Books

The devastating outbreak of Ebola that began a year ago has now claimed the lives of more than 10,000 people according to the World Health Organization (WHO), mainly in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea. Incidents have steadily declined, but dozens of new cases are still being reported each week. Authorities in Sierra Leone recently ordered a three-day national lockdown to prevent spread of the disease (ending 29 March) in the latest attempt to stem its progress. Nonetheless the country has declared a goal of zero infections from Ebola by April 2015.

The scene of so many human tragedies and loss to families has gained worldwide attention in the midst of attempts to manage a crisis in public health and to avert an even greater disaster. To understand an ordeal of this kind we inevitably search for historical parallels and ways of imagining the experience. Perhaps the most vivid account of such circumstances appears in Daniel Defoe’s novel, A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), his description based on historical sources of the Great Plague of London in 1665 in which upwards of 100,00 lost their lives. Defoe wrote the work in the shadow of another plague epidemic, the Marseille outbreak of 1720-23 which caused the deaths of a similar number.

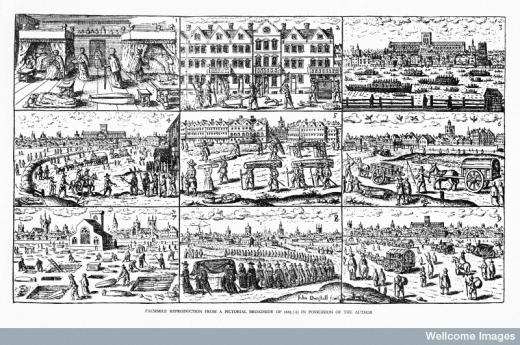

Credit: Wellcome Library, London

Woodcut 1924

From: The Great Plague of London

By: Bell, Walter George

Published: John Lane, London 1924

Collection: General Collections

Defoe makes use of a circumspect narrator, known only as H.F., who observes events first hand as the disease moves across the parishes of the City of London, registered in weekly ‘Bills of Mortality’. Confusion reigns in the capital as panicked residents flee with their belongings, while others – mainly servants, the poor, and courageous public officials – remain behind. The plague carts rumble continuously through the streets, with calls for the dead to be brought out, transporting victims initially to graveyards and then to sites of mass burial. H.F. vividly conveys the sound of grief in cries from London houses and the discovery of grim evidence of the plague’s effects.

Several striking connections with the Ebola crisis appear, not least the spectacle in these different historical moments of bodies left in the street with people too fearful to move them. Defoe makes clear that the normal observances accorded to the deceased had to be suspended. In Africa, the WHO issued formal instructions to stop the practice of families washing the bodies of the dead, according to religious tradition, in order to prevent the virus from spreading. At the same time, the proximity of burial grounds to inhabited areas became a cause of controversy in some cases in Africa, while locations in London in 1665 had to be found that were close enough to manage logistically while far enough away to inhibit infection. (In a memorable scene in Defoe’s novel, H.F. is unable to overcome his curiosity and goes out to inspect one place of mass interment in Aldgate, risking his own life in the process.)

The recent lockdown in Sierra Leone was designed to prevent interaction between people and to minimize the threat of further contagion, but it has still been criticized for its severity. In any case, officials continued to allow people to attend religious services and to thus to congregate. H.F. notes that church going continued at high levels in 1665 despite the fear of close contact, and even that traditional differences between members of the established church and dissenters diminished.

Defoe’s book shows that quarantine practices were difficult to maintain and that confining affected families to their houses, a remedy implemented at the time, proved ineffective. One of the major strategies employed by the WHO and Médecins sans Frontières has of course been precisely to isolate disease areas and to restrict contact, but this too has been difficult to achieve. The scale of the outbreak is also vastly greater in geographical terms.

Health officials have also concentrated on the production of a vaccine against Ebola. In Defoe’s time, uncertainty prevailed over how the plague communicated itself. H.F. concludes that it spreads by infection but exactly how remains a mystery. He concludes that it occurs

by some certain streams or fumes, which the physicians call effluvia, by the breath, or by the sweat, or by the stench of the sores of the sick persons, or some other way, perhaps….[these] effluvia affected the sound who came within certain distances of the sick, immediately penetrating the vital parts of the said sound persons, putting their blood into an immediate ferment, and agitating their spirits….

In this context, quacks and mountebanks took advantage and sold all manner of remedies and preventatives, lamented by the sceptical H.F., who takes some satisfaction in noting the high death toll among them. Whether such cures have been peddled in West Africa I can’t say, but one blog advocating scientific medicine has taken aim at internet proponents of homeopathy and a range of supposed redresses in the form of selenium, vitamin C, Vitamin D, iodine, magnesium, estradiol, infrared radiation, sodium bicarbonate, cannabis, coffee, fermented soy, and salty drinking water.

Amid the horrors of the Ebola epidemic, one of the harrowing features has been the closing of borders to refugees trying to evade the disease, notably in the Ivory Coast but also internally in different countries where isolated ‘plague villages’ have emerged. Health workers have also sometimes become the object of suspicion as possible agents for disseminating the illness. Defoe captures the dilemmas of self-preservation by telling the story of the flight from Wapping in London of three men driven to extremity – a carpenter and two ex-sailors, brothers who had taken up baking ship’s biscuit and sail-making between them. They were joined by others at Hackney to head out in the direction of Essex. At Walthamstow their access is blocked but they head on to Epping where they again meet with resistance from worried townspeople. They set up a camp outside and survive there on their wits, pooling their skills and receiving occasional charity from villagers who leave food and resources at a safe distance for them to collect. They form a kind of model community in middle of the most distressing circumstances.

Defoe shows us the chilling prospect of a communicable disease whose progress challenges the resourcefulness of citizens, doctors, nurses, and public officials. He also shows the human reality of contending with an epidemic, described through inset stories set against the wider tableau of a catastrophic moment. Nearly three hundred years after he published the book it remains a source of insight as Ebola completes its own plague year.

Update: DNA confirms cause of 1665 London's Great Plague, BBC, 8 September 2016