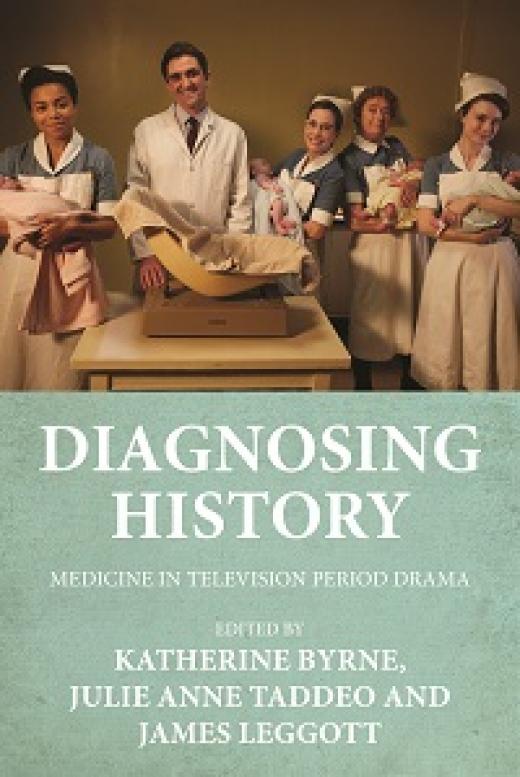

During the COVID 19 pandemic public health preoccupied us all like never before. Conversations around vaccination, treatment, hospital resources and the sacrifices of increasingly exhausted medical professionals dominated our screens and our thoughts. At the same time, desperate for distraction, we all watched a great deal more television than usual. Our recent book, Diagnosing History: Medicine in Television Period Drama (Manchester UP, 2022), explores the complex, symbiotic relationship between the two. Long before the pandemic began, viewers have been fascinated by medical television and medical plotlines, with some of the longest running and most popular shows of all time being hospital-set dramas like ER (1994-2009), or docudramas like One Born Every Minute (2010-) and Your Life in their Hands (1958-2005). We, however, looked specifically at television period dramas, which we had noticed were usually either exclusively medical in focus (most famously Call the Midwife, (2012-)) or contained important medical plotlines or characters that were physicians or nurses (almost every other period drama!). When revisiting or reworking the past, including stories about public health and the sick or recuperating body seems essential to a successful show. Even the most glossy and rose-tinted of “heritage” dramas, Downton Abbey (2010-2015) contained some hard-hitting medical subplots like the Spanish ‘flu and the death of Lady Sybil in childbirth; more gritty ones, like Harlots (2017-) explored the representation of syphilis; Poldark (2015-2019) portrayed mental health problems and their treatments. Such a wide range of illnesses across such very different historical shows suggests that medicine provides an accessible and fascinating way of accessing the past, or even, perhaps, that history is at its most compelling for the public when navigated through the diseased or suffering body. By focussing upon it, these shows are able to explore the class and gender issues that impacted upon patients and their care, and the moral implications of the scientific advances that improved so many lives – but often at a cost.

These shows do not only provide a window into our shared corporeal past, however. They frequently provide insights into our present day and the debates that surround contemporary healthcare systems. For example, Call the Midwife is a loving, nostalgic tribute to the importance of the NHS, arguing for the vital role it played, and still plays, in the lives of ordinary people in the UK, at a time when it is under threat from privatisation. Specifically, this show’s portrayal of an often undervalued profession reminds us of the huge importance of midwifery to the community, throughout history and today. More problematically, however, in constructing straightforward, unassisted childbirth as something commonplace, desirable and accessible to all, this show disseminates the profession’s dominant ideology of “natural birth”, something which is currently hotly debated because its tragic fallout has dominated the news recently[1]. Similarly, Outlander’s (1991-) central character, time-travelling nurse Claire, provides timely commentary about women’s health in the episodes where she dispenses advice about contraception and abortion to women otherwise denied these services. Even the gothic depiction of syphilis and the stigma attached to it, in The Frankenstein Chronicles (2015-2017) makes us confront that which is still endured by those suffering from HIV/AIDS in the twenty-first century. These shows may be historical in setting, but they remind us that many of the issues they deal with are still relevant. We may be lucky enough to have antibiotics, vaccines and anaesthetics now, but in most other ways we fall short of the care we should be able to provide. Even in the most developed countries, women are still denied access to birth control, people with certain illnesses and disabilities still are discriminated against, and maternity care is still dominated by ideology (and cost) not what is best for the mother. And, of course, that is quite aside from the inequalities in public health provision in poorer nations around the world – inequalities that have been highlighted by the pace of the COVID vaccination programme.

One of the key things that emerged from our book is television’s fascination with the figure of the medical practitioner. Often heroes, frequently misunderstood pioneers, and occasionally sadistic villains, doctors are always at the centre of these shows and our public consciousness . They are too often white and male, of course, for period television is disturbingly still happier with the portrayal of women in nursing roles, and as Kevin McQueeney’s chapter argues, racism and the history of medicine frequently go hand-in-hand[2].

Those problems notwithstanding, period drama shows doctors breaking the rules, working at the cutting edge of their professions, and often risking their lives and their sanity to save others, reminding us of the high personal cost of the scientific breakthroughs we enjoy in the twenty-first century. These representations predate, but naturally reinforce the way we now think about those medical professionals who made such personal sacrifices during COVID. Of course, television has long made these portrayals more “human” and flawed by adding in stories of addiction and personal trauma, plotlines which seem melodramatic but which we are increasingly understanding likely reflect the real-life coping strategies of those who work under such pressures.

Chapters in our edited collection explore the demons of surgeons like the tormented Dr John Thackery (Clive Owen) from The Knick (2014-2015) and the struggles of altruistic doctors like Enys from Poldark, whose compassionate patient-focused views are so far ahead of his time. Television also loves the evil doctor corrupted by power, however, and Penny Dreadful (2014-2016) and The Frankenstein Chronicles both feature characters whose pursuit of knowledge has long overshadowed their morality and humanity. This is a suspicion which has dogged doctors since at least Mary Shelley’s day, and these characters reflect our continuing anxiety about a profession on which we depend so heavily, and which has such influence over our lives. Medicine pursued for the right purposes creates the compassionate characters of Doctor Quinn Medicine Woman (1993-1998), or Dr Turner in Call the Midwife, but these figures are shadowed by those tainted by greed or arrogance. All these shows remind us of the need for medicine to rise above financial concerns or personal advantage, but the constant struggles of these fictional doctors show how difficult such an ideal has always been to achieve.

Period drama is often accused of fostering nostalgia for a past that has never existed, and it is perhaps only in their medical plotlines that this is not true[3]. These shows can make us grateful for our more sophisticated present, one where Lady Sybil would not have died of preeclampsia (certainly not given her privileged position!) and where new vaccines can be created in a lab in weeks. Shows like Call the Midwife do, however, make us wistful for the personal, accessible care associated with the birth of the NHS, which has got lost in much of our public health today. We cannot afford to be complacent about progress, for period television reminds us that independence from financial concerns, individual endeavour and sacrifice, and patient-focused compassion are as vital, yet precarious, as they have been at any time over the last two hundred years.

[1] BBC News: “Shrewsbury maternity report: Uncovering the biggest NHS maternity scandal”. 2ND April 2022. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-60957400 (accessed 28/04/2022)

[2] McQueeny, K, The Black Doctor on the Historical Small Screen” in Byrne, K, Leggot, J and Taddeo (eds.) Diagnosing History. Manchester UP, 2022.

[3] Higson, A 2003, English Heritage, English Cinema: Costume Drama since 1980. Oxford University Press, Oxford.