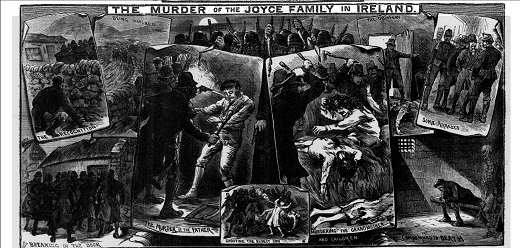

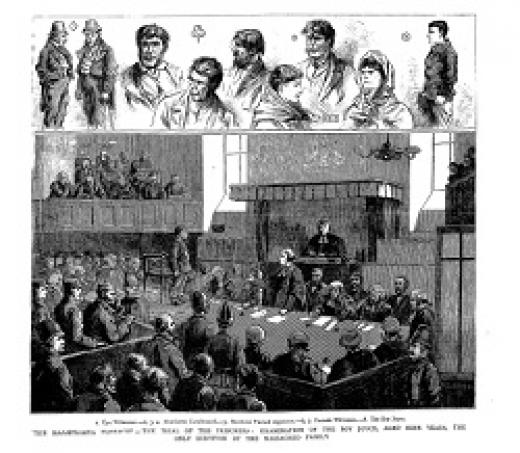

Two new books, a docu-drama, and a presidential pardon, have brought the late nineteenth-century Maamtrasna murder case back to public prominence in recent years. The incidents they describe began on 17 August 1882, with the murder of five family members in Maamtrasna, Co. Galway. Eight men were tried and convicted, on the basis of perjured testimony. Three of them were executed and the others imprisoned for life. Two of the convicted prisoners and two informers later admitted the innocence of Maolra Seoighe (Myles Joyce), who had been put to death. In 2018 on the advice of government, President Michael D. Higgins formally pardoned Seoighe. Part of the injustice was the fact that the trial took place in English, with only a very limited interpretation service provided to the defendants, who were primarily monoglot Irish speakers.

The book by former Irish language commissioner Seán Ó Cuirreáin, Éagóir (2016), began this new attention (itself taking inspiration from Jarlath Waldron’s 1992 Maamtrasna: The Murders and the Mystery), followed by Ciarán Ó Cofaigh’s feature-length docu-drama based on Ó Cuirreáin’s work, Murdair Mhám Trasna (broadcast on TG4 in April 2018). Margaret Kelleher’s prize-winning The Maamtrasna Murders: Language, Life and Death in Nineteenth-Century Ireland (2018), is the most recent study, drawing on new archival research.

As a lecturer in Irish, the case has long interested me. In 2008, while teaching at NUI Galway for the BA in Irish, I worked closely with Seán Ó Cuirreáin to develop appropriate teaching materials to make a complex and demanding topic accessible and interesting to the average contemporary student not prone to excessive background research or engagement – a tall order, you might say. Getting students of Irish to brainstorm what might be meant by language rights was difficult as only the small minority who come from what might be described as activist backgrounds had ever given it any consideration.

Seán was researching his book on Maamtrasna at the time and suggested that I include James Joyce’s journalistic commentary from 1907 on the hanging of Maolra Seoighe, an article published in an Italian newspaper when Joyce was living in Trieste. Although Joyce’s account contains many historical inaccuracies, it is nonetheless an arresting and jolting reflection on the sheer injustice done to the three men who were hanged outside Galway Jail in 1882. Reading this aloud in class at the start of every academic year has never ceased to be moving both for me and students:

When the questioning was over, the guilt of the poor old man was declared proved, and he was remanded to a superior court which condemned him to the noose. On the day the sentence was executed, the square in front of the prison was jammed full of kneeling people shouting prayers in Irish for the repose of Myles Joyce’s soul. The story was told that the executioner, unable to make the victim understand him, kicked at the miserable man's head in anger to shove it into the noose.

The classroom discussion that follows almost inevitably reveals a sense of awakening among students about the issue of language rights, how they could literally be a matter of life or death in late nineteenth-century Ireland and how they continue to be relevant today. I’m not claiming credit for turning out a revolutionary cadre every year – although that wouldn’t be a bad thing – but I don’t believe that it is possible to study a minoritised language such as Irish without considering the pressures on its speakers, something never considered by monolingual speakers of hegemonic languages. As Margaret Kelleher so eloquently puts it, this involves recognising the ‘processes of attempted usage, prohibition and the failure to be heard’. The erasure or the silencing of speakers of minoritised languages such as Irish continues to resonate today, and is at heart of the study of the links between language ideologies and language practices.

And that leads me to the relevance of the stories told by Seán Ó Cuirreáin, Margaret Kelleher, Ciarán Ó Cofaigh, and others before them for the contemporary study of the sociolinguistics of Irish. They provide a crucial historical context for the contemporary study of language rights, language legislation and the revitalisation of minoritised languages in general. I welcome Margaret Kelleher’s use of critical sociolinguistics to throw light on the conceptual deficiencies inherent in long-standing linguistic categories such as ‘language’, ‘bilingual’ and ‘multilingual’ and her attention to the ‘messiness’ of sociolinguistics and language shift itself, as Monica Heller and other scholars of sociolinguistics have characterised it.

To these supposedly stable categories I would add the concept of ‘speaker’ which is equally slippy and problematic as we have discussed in our own ongoing research project on ‘new speakers’, people who often straddle perceived boundaries between ‘native speakers’ and ‘learners’. The history of ‘transitional bilingualism’ in the nineteenth century identified by Kelleher and others such as Liam Mac Mathúna is a useful lens for understanding not only the linguistic dynamics of the period, but our shifting and fluid linguistic ecosystems today.

Although the British census in Ireland was unusual in recognising the fact that some people were bilingual, it simply could not capture what was happening in the interstices between Irish and English, those occluded spaces where people spoke varying degrees of both languages at different times and in different milieus, often changing over the course of a lifetime and within generations of the one family. These linguistic twilight zones were dismissed by official ideology as contaminated spaces inhabited by deficient semi-speakers.

Independence in 1922 did not change that dynamic: the Irish census continued in the same vein and the imprimatur of the Irish Folklore Commission and the Dublin Institute of Advanced Studies continued to valorise and prioritise what were deemed to be the least corrupt native speakers of Irish. I have looked at this dynamic in the case of the ‘Breac-Ghaeltacht’, the speckled or partial Gaeltacht of the Irish Free State, a kind of broken and breached linguistic buffer zone around the ‘Fíor-Ghaeltacht’, the true Irish speaking area, and all of the ideologies associated with that. But as in the case of Maamtrasna, other less official sources in the early twentieth century can help us understand the transitional bilingualism of the Breac-Ghaeltacht: for instance, the diaries of the folklore collector from West Waterford Nioclás Breatnach, whose contemporaneous accounts of his travels throughout the Déise contain intriguing accounts of fluctuating language practices and ideologies in the region during the 1930s.

Under the simplistic binary surface of Irish versus English was a fascinating patchwork of beliefs and practices invisible in official quantitative sources. Failure to recognise such hybrid spaces not only erases the historical reality of transitional bilingualism, but from a language revitalisation perspective it also devalorises people who have skills in the minoritised language which could potentially be developed. The sociolinguistics of minoritised languages needs to pay greater attention to how such unofficial sources can help us to understand language shift and indeed to interrogate the ideology inherent in the term itself. While Irish undoubtedly collapsed as a community language over the nineteenth century, the language shift was far from inevitable, as Kelleher’s book points out, and the fact that we are still talking about language rights today is a reminder that such shift is not entirely complete.

These themes remain relevant to contemporary discussion about language rights in Ireland. The Official Languages Act of 2003 created a limited number of rights, including the right to use Irish in any pleading in any court. The section of the Act also stipulates that anyone using that right cannot be placed at a disadvantage or be liable for costs of interpretation or translation if these are required. This is a significant right, standing in stark contrast with the historical injustices of Maamtrasna, and yet we know that the take-up of Irish in court cases is much lower than with immigrant languages such as Polish. Competence in English is undoubtedly a factor here, with many Irish speakers – even those who may consider that their Irish is better than their English – choosing to speak English in order to access state services including the courts if that is required.

The argument that ‘you all speak English anyway’ is frequently thrown at Irish speakers as a way of undermining their claims to any service in Irish, usually by people who are themselves resolutely or even proudly monolingual. Such an ideology of contempt is of course a long-standing part of the processes that have led to the historical minoritisation of such languages in the first place. It is anachronistic and unjust, in an increasingly multilingual world, to deny someone the use of either their ancestral language or the language with which they most identify because of their ability in another language.

At the recent trial of Catalan separatist leaders in Madrid, witnesses who wanted to speak Catalan were warned recently by the judge to speak Spanish or be thrown out of the court, a statement chillingly reminiscent of the Franco years and a reminder of how Spain is utterly incapable of accepting the fact that it is a multilingual state. In the Irish case, there is a powerful dynamic at play, ingrained in the linguistic culture of Irish since the very beginnings of language shift: the deep-seated belief among Irish speakers that the state (first the British and now the Irish state) is either unwilling or simply unable to serve them in Irish, even despite the legislative changes of recent times. Add to that the overwhelming dominance of English and the stress of dealing with the law and it becomes understandable why an Irish speaker would not take up rights that are supposed to be available unambiguously.

It is eight years since the government announced a review of the Official Languages Act and shamefully, a revised Bill has yet to be published although the heads of a Bill were agreed two years ago. Almost one hundred years after the revival of Irish was declared as one of the founding aims of the state, we need a revised Act to deal with the structural weakness in the provision of services in Irish as well as a recruitment strategy of people with Irish language skills. We also need a parallel strategy of tackling the disbelief among Irish speakers that they can use Irish with the state in the first place. Finally, as researchers we also need constantly to attempt to understand how we got here and how barriers to the promotion of minoritised languages such as Irish are both created and potentially overcome.

Molaim go hard an obair atá déanta ag Margaret Kelleher, ag Seán Ó Cuirreáin agus ag Ciarán Ó Cofaigh le blianta beaga anuas chun aird an phobail a tharraingt ar na ceisteanna tábhachtacha seo agus gabhaim buíochas le hInstitiúid de Móra as an gcuireadh chun cainte agus as an ócáid seo a reáchtáil.

These remarks were delivered as part of a panel discussion on ‘The Maamtrasna Murder Case: Politics, Language, Identity’ held at the Moore Institute for Research in the Humanities and Social Studies, NUI Galway on 22 May 2019.