National Library of Ireland Flickr account

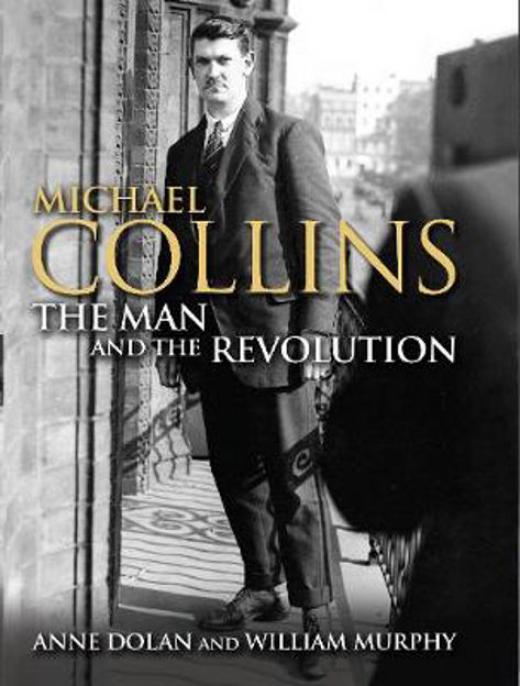

In November 2021, the family of the late Liam Collins, a nephew of Michael Collins, loaned a set of his uncle’s diaries to the National Archives of Ireland (NAI). There are five, dating from the years 1918 to 1922. Immediately, Zoë Reid at the NAI set about the task of conserving and digitising the diaries with the purpose of making digital versions available to the public at Bishop Street in Dublin and at the Michael Collins House Museum in Clonakilty. Meanwhile, as authors of a 2018 biographical study of Collins, we responded to an invitation from Orlaith McBride, director of the archives, to produce a book that would introduce the diaries. The result is Days in the life: reading the Michael Collins diaries, 1918-1922, published by the NAI in conjunction with the Royal Irish Academy.

The first three (1918-1920) are working pocket diaries. In the case of 1918, for example, T. J. & J. Smith Ltd of Charterhouse Square, London produced it. Smith was a leading manufacturer and this one belonged to a range the company promoted as ‘Automatic Self-Registering’ diaries. The defining gimmick was a steel spring which held his pencil in place, allowing it to double-job as a bookmark of wood and lead. This ensured, as the ads explained, ‘The page last written upon immediately found on opening the Book, with Pencil ready to hand.’[1] The pocket diary market had been growing rapidly since the 1890s, encouraging companies like T. J. & J. Smith to produce an ever greater variety, designed and branded to meet a range of needs, an array of self-images.[2] This one said clever, business-like, practical; ideal for the busy office manager and revolutionary.

It was small, 12cm long, 7.5cm wide and less than a centimetre deep: snug in his hand and safe in his pocket. Each week laid out across facing pages, Sunday to Saturday in bold green print and in separate boxes, framed in red and lined in grey. In 1919 he switched to a Collins’ Gentleman’s Diary No.174. It afforded him a page a day and, consequently, was slightly thicker but the purpose did not change.

These diaries were functional and, in that sense only, essential. They did not give his life meaning. He did not interrogate himself nor did he explain himself to anyone else, instead these pages helped him to get to meetings on time, most of the time. Do not imagine careful compositions, products of pause and contemplation, but hurried notes, necessary lists, addresses, aides-mémoire, donations, calculations, things to do, things not done, accumulations, asides and abbreviations.

Indeed, there are very few entries at all for the final months of 1920 and the diary for 1921 begins only in October. Perhaps, he had come to consider carrying a pocket diary as simply too dangerous then. On Wednesday 12 October, during the Treaty negotiations in London he resumed. From that day till the end he was at it again; noting, listing, recording, creating what were daily to-do lists on the somewhat larger pages of a notebook which he transformed into a diary by writing the day and date at the top.

Reading the diaries has an interesting effect. Some years pass quicker than others. The Irish revolution rushes: the Rising, election, Dáil, war, truce, Treaty, split, civil war, end. In most tellings of the Irish revolution the work of months, years contract into a sequence of dramatic episodes, and hindsight brings a momentum many who lived through 1916-23 might never have recognised. Revolutions make good stories, and Michael Collins above all kept the pages turning fast.

But Collins’s five diaries stop this momentum in its tracks. His days, measured out in hours, in half-hours, in meetings and committees and so many letters sent, are each one long and full and followed by another just as long and just as full again. The working week of Monday to Saturday, borrowed many of his Sundays in 1918 and 1919; by 1921 Collins stole back only the odd day for himself.

Full as they are, the diaries of 1918 and 1919 reflect largely his ‘second work day’, the one that began when the staff in the many different offices he oversaw had gone home.[3] The diaries mostly record the times and places he needed to remember, not the steady grind of daily work. ‘8 O’C[lock] at 44, 8.30 at no 41’, ‘6 O’C No 6 Election C[ommi]ttee. 8 [O’C] Organisation Cttee’; 6.00, 7.30, 8.00, 8.30 in one evening; 10.00, 10.30 at night; once two meetings at the same time – the diaries account for evenings filled, weekends travelling, money gathered.[4] They reflect the scale of Collins’s voracious appetite for more and more work.

The diaries map him at addresses, and they put him on the clock. His weeks were shaped by those numbers, numbers that meant addresses: 6 was Harcourt Street and Sinn Féin headquarters; 32 was Bachelor’s Walk and the office of the Irish National Aid and Volunteer Dependents’ Fund (INA & VDF); 35 was Gardiner Street, an Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) meeting place; 44 was Mountjoy Street, a place to gather, a home of sorts for a while.[5] There were other numbers, and, like the initials, they signified just enough to remind him of where he needed to be and who he was to meet. The slightly worried, perhaps exasperated, ‘Mtg today @ where?’ of 10 September 1920 was a rare case of Collins losing track.[6] As 1921 became 1922 phone numbers meant people, particularly in London, but in Dublin too. He worked in a world of initials, of Christian names, and in the pages of his diaries some names recur while others come and go, important for a time, but quickly overtaken by the urgency of other things.

Over several months, our work became a journey into the ravel of the source. The book we produced would have been different if he had left us contemplative diaries, but these gnomic, cryptic, appointment books demanded a different approach. In the challenge of their form, they made us look again. More than that, his diaries change the angle of vision on Collins and the wider revolution. These little books, which ordered out his individual days, at once speed time up and slow it down. It is as if someone is showing us a newsreel, often too fast and then suddenly too slow. Amidst a maelstrom of work and effort come moments in stunning freeze-frame. We get the relentless pace of revolution, but also the slow grind of individual days. We see him interacting with so many people; he rushes about. Yet he experiences all of it in the midst of the quotidian, the personal, and the mundane.

There are patterns yes, but always alongside the pulse and the mess, the contingent and the unresolved. The last page we have is for a Sunday, 6 August 1922. It begins ‘I Inspection Barracks today’, and continues ‘II Mass’, before it ends ‘III ’. [7] He seems farther away and closer to us in the words and in the gaps, in I and II but also III, the almost written down.

[1] https://stors.tas.gov.au/download/CRO2-1-9 [accessed, 11 May 2022].

[2] Joe Moran, ‘Private lives, public histories: the diary in twentieth-century Britain’, Journal of British Studies, 54:1 (2015), pp 143-4; Anthony Letts, ‘A history of Letts’ in Letts keep a diary: a history of diary keeping in Great Britain from 16th-20th century (London, 1987), p. 31.

[3] Peter Hart, Mick: the real Michael Collins (London, 2005), p. 250.

[4] Diary of Michael Collins, 12 Jan. 1918; 20 Feb. 1918; 28 March 1918; 12 May 1918, 21 May 1918; 9 Feb. 1918 ‘Céilide Mansion House at 8. 8 O’Clock no 41’.

[5] Joseph E.A. Connell Jr, Michael Collins: Dublin 1916-22 (Dublin, 2017).

[6] Diary of Michael Collins, 10 Sept. 1920.

[7] Diary of Michael Collins, 6 Aug. 1922.