In recent commentary, academic and otherwise, on the centenary of Northern Ireland, there has been no reference to the fact that the imposition of partition on the island of Ireland in 1920-21 was facilitated by the absence of a strong Irish nationalist party at Westminster, the consequence of Sinn Féin’s policy of not taking their seats in the House of Commons – their policy of abstentionism.

It had become obvious very early on in the Irish Home Rule crisis of 1912-14 that some form of partition was in the offing. The extent of the area to be excluded from the jurisdiction of a Dublin parliament and the duration of that exclusion were the subject of intense debate right up to the inconclusive Buckingham Palace conference in July 1914, just before the outbreak of the First World War. The bottom line for John Redmond and the Irish party at Westminster was that partition should be strictly temporary and limited to the four north-eastern counties that had clear Unionist majorities. That wasn’t enough for the Unionists, and so no settlement was agreed at that time. The point to note is that the Irish party at Westminster were in a position to block the Unionist demands despite the threat of violence by Ulster Unionists, backed by the British Conservative party.

The reason for this was that the second of two indecisive general elections in 1910 had given the Irish party, with 74 seats in the House of Commons, the balance of power. This enabled them to get Home Rule back on the political agenda for the first time since Gladstone's fourth and final premiership came to an unhappy end on the issue of Home Rule in 1894. The Liberal government took up the cause of Home Rule after 1910 out of political necessity – not with any Gladstonian moral purpose. In short, they were forced to do so by the parliamentary arithmetic.

Moreover, as James Doherty points out in his recent study Irish liberty, British democracy, there was solid support for Home Rule among the British public, particularly the rank-and-file of the Liberal party – as distinct from the party’s leadership. He presents an impressive array of material from pamphlets, newspapers and periodicals to support this contention. He shows that, with the veto of the House of Lords abolished by the 1911 Parliament Act, passage of a Home Rule Bill was widely regarded throughout Britain as a test of the new political dispensation – in other words, a test of whether the will of the House of Commons would prevail. He elaborates as follows: ‘the essence of Unionist opposition, Liberal writers asserted, was an effort to preserve oligarchy, while Home Rule was a struggle to assert democratic rights ... the assault on Home Rule [was] a fresh eruption of the constitutional struggle between peers and people, one that sought to turn the democratic tide that had been rising for decades.’[1]

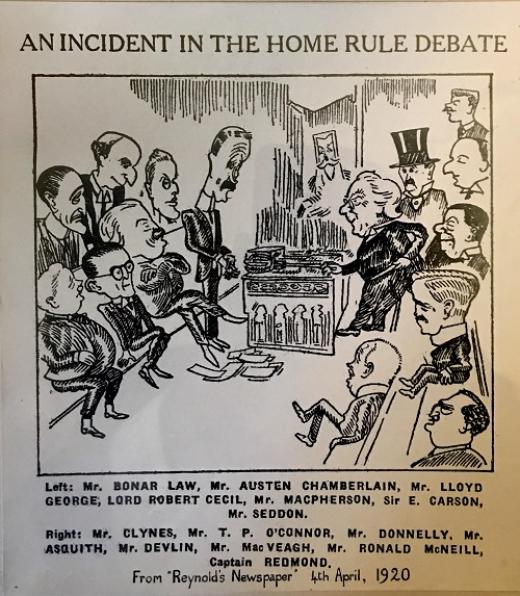

Redmond and the Irish party were, therefore, in a much stronger position to secure Home Rule with minimal concessions to the Ulster Unionists than is generally recognised. Public opinion, as well as parliamentary arithmetic, constrained the government from yielding to Ulster Unionist pressure. This remained the position even after the formation of the coalition government in Britain in 1915. That brought Conservatives and Unionists into the cabinet in order to boost the war effort, and it meant that the Irish party lost the balance of power in Westminster. The Irish party’s position was, however, still powerful enough to block Lloyd George’s proposals when, in the weeks after the Easter Rising in 1916, he attempted to implement Home Rule with partition as a ‘quick fix’ response to the Rising – in the words of D.G. Boyce, ‘an arrangement that would paper over the cracks’.[2] They scuppered the deal once it was revealed that Lloyd George had been duplicitous, promising the Ulster Unionists that partition would be permanent while assuring the Irish party leaders that it would be temporary. Quoting Boyce again, Lloyd George ‘did not shrink from making contradictory promises’ in an effort not to repeat the failure of the Buckingham Palace conference in 1914.[3]

The leverage over British government policy that Irish nationalists enjoyed was lost when Sinn Féin swept the Irish party aside in the 1918 General Election, thereby removing all but a few Irish nationalist voices from the only forum – namely, the House of Commons – in which the future of Ireland was going to be settled. The alliance between the British Liberal party and Irish nationalists was now redundant – and, in addition, Irish nationalists were denied a base from which to rally British public opinion. The government were thus enabled to adopt the Government of Ireland Act 1920 without any regard to Irish nationalist sentiment. The Act was drawn up by Sir Walter Long, a Southern Irish Unionist who had became chairman of the Irish committee of the cabinet. In the absence of Sinn Féin from Westminster, Long had – to quote Ronan Fanning’s FatalPath – ‘a blank cheque to propose partition’ and give Ulster Unionists precisely what they sought.[4]

Would partition have been avoided in 1920-21 if Irish nationalists had been represented in the House of Commons in the same numbers as in 1910-18? Their position would certainly have been weaker than in the earlier period because of the thumping majority enjoyed by the Lloyd George coalition after the 1918 General Election. Also, the strength of the Ulster Unionist determination to resist Home Rule – always underestimated by Irish nationalists of every hue – can never be gainsaid. Nevertheless, at least one old Irish party stalwart thought partition would not have happened but for the rise of Sinn Féin. In his memoir Parnell to Pearse, John J. Horgan wrote: ‘We constitutionalists had been wisely prepared to make large concessions in order to avoid the division of our country which we believed to be the final and intolerable wrong. The price of our successors’ triumph was Partition – an Ireland divided into a state which is not coterminous with the country, and a province which is itself dismembered.’[5]

[1] James Doherty, Irish Liberty, British Democracy: the third Irish Home Rule crisis, 1909-14 (Cork, 2019), pp. 79 & 92.

[2] D.G. Boyce, ‘How to settle the Irish question: Lloyd George and Ireland, 1916-21’, in A.J.P. Taylor, Lloyd George: twelve essays (New York, 1971), p. 139.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ronan Fanning, Fatal Path: British government and Irish revolution, 1910-1922 (London, 2013), p. 204.

[5] John J. Horgan, Parnell to Pearse: some recollections and reflections, with a biographical introduction by John Horgan (Dublin, 2009), p. 354.