https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/our-plan-to-rebuild-the-uk-governments-covid-19-recovery-strategy/our-plan-to-rebuild-the-uk-governments-covid-19-recovery-strategy).

On March 18th, as Covid-19 spread across the United States, Donald Trump declared himself a “wartime president”. Like many of his fellow leaders, he opted for metaphor amidst the crisis, enhancing his status while underscoring the severity of the situation. The pandemic has proved a fruitful ground for figurative language, with metaphors, similes, and other comparisons defining our relationship to a complex and tragic reality. Politicians have not been slow to exploit this resource, but the sheer density of images requires some comment and consideration.

War provided an organising image from the start, surfacing in speeches by Trump, Emanuel Macron, and Boris Johnson. Trump identified the virus as the “invisible enemy”, combatted (ostensibly) with military resolve. In a press conference only last week, Matt Hancock, the erstwhile UK Health Secretary, repeated the theme, commenting that “history has shown that understanding an enemy is essential to defeating it”, and recommitting to “this fight against our common foe”. Critiques of the language of war have surfaced from different sources, but there is more to it than just self-aggrandisement. War suspends ordinary life, it requires the energy and dedication of the society as a whole, and it sees the state at its most active, entitled to impose a lockdown, declare an emergency, and to borrow unprecedented amounts to fund its needs. It is an occasion for the heroic. Wars can also be won, and victory over enemies declared, a scenario that coronavirus unfortunately does not lend itself to.

Nor do politicians exercise any kind of monopoly here. The tendency to configure the predicament as a battle has been widespread, even in common speech. Doctors, nurses, and hospital workers fighting the disease have been identified as occupying the front line, along with others in support capacities (cleaners, supermarket workers, delivery people). The image confirms the essential nature of their contribution (even without adequate protective gear required for such a fight).

In the UK, Boris Johnson – a former columnist, with writerly inclinations – has shown a penchant for metaphor during the crisis. When he returned from his hospitalisation following infection by Covid-19, he made a public address in front of No. 10 by offering the somewhat predictable claim that “We are now beginning to turn the tide”, without recognising the unfortunate fact that tides have a habit of coming back in again. He went on to draw the following comparison:

If this virus were a physical assailant, an unexpected and invisible mugger, which I can tell you from personal experience it is, then this is the moment we have begun together to wrestle it to the floor.

Johnson cast himself in the role of victim – an innocent bystander who did not invite his fate with rash behaviour – assaulted by an unseen aggressor. Perhaps this was the only way to communicate vulnerability without dilating on the horrors of the disease or admitting culpability given his habit of doling out handshakes at a rugby match in the lead up to his illness.

Johnson’s next contribution came when he resumed attendance at the daily press conference on April 30th. In his opening remarks, he declared: “We are past the peak, and we are on the downward slope.” No marks for originality here, but an apter image to the tidal metaphor under the circumstances. He then went on to add some baroque flourishes:

We’ve come through the peak, or rather we have come under what could have been a vast peak, as though we have been going through some huge alpine tunnel. And we can now see sunlight and the pasture ahead of us, and so it is vital that we do not now lose control and run slap into a second and even bigger mountain.

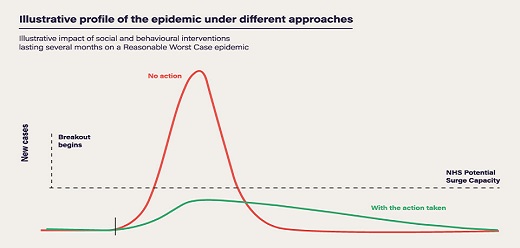

The lines on graphs projecting massive infection rates and fatalities if no action were taken evidently suggested an Alpine topography to him, successfully tunnelled under by the government’s efforts. To incentivise commitment to the strategy, he embellished things with a pastoral vision, but descended into farce with the warning of another mountain looming on the other side. The image recalls one of his early forays before the virus took a major grip in the UK (March 12), when he noted the determination to “squash the sombrero” in reference to the heightened curve. It transpires that the only sombrero flattened in the event was Johnson himself.

In other contexts, the metaphors have been fashioned to offer comfort. Johnson’s Downing Street press conference on May 25th saw him commend the government’s effort in “wrapping our arms around every worker in this country with the furlough scheme”. The imagery, offered spontaneously in answer to a question, was more convincing than Hancock’s ill-judged prepared remarks in the daily briefing ten days earlier when he claimed that “Right from the start we have tried to throw a protective ring around our care homes” – either a disingenuous statement or an admission of incompetence given that, by his own figures, 11,560 people had died in such facilities.

If Johnson has indulged a taste in metaphor (praising the staff treating him at St. Thomas’ Hospital for pulling his “chestnuts out of the fire”), Donald Trump has largely confined himself to familiar territory of hyperbole and self-praise. When he endorsed the curative powers of strong sunlight and injection of bleach he engaged simultaneously in extreme literalism and a metaphorical transfer of the external to the internal. He mused about bringing “light inside of the body, which you can do either through the skin or in some other way”, before speculating on the merits of bleach “by injection inside or almost a cleaning.” The process, steeped in magical thinking, relied on the disinfectant’s power to cleanse the inside as efficiently as Clorox on a countertop.

Trump made a freewheeling contribution on that occasion, but his virtual “town hall” meeting on coronavirus in front of the Lincoln Memorial with Fox News on May 4th was a calculated event designed to establish a (frankly outrageous) symbolic connection between himself and the sixteenth president. Metaphor and symbol occupy similar territory, with symbols perhaps replete with wider associations. But Trump clearly wished to draw together metaphorical resonances with the dignity, wartime leadership and martyrdom of his predecessor in seating himself in such company. Others have been more subtle in their approach. Jacinta Ardern, New Zealand’s prime minister, has won praise for her informal style in addressing citizens by Facebook. On March 25th she appeared in a Covid Q&A at home, wearing a comfortable green sweatshirt, and apologised for the attire, saying “it can be a messy business putting toddlers to bed”, in reference to her nearly two-year-old daughter Neve. The connection may have been innocent or pre-determined, but it positioned the nation as infant child, cared for by a nurturing mother, safe in a domestic space.

If we leave aside the sphere of politicians, there is a larger story to be told here. Figurative language is a way of mediating our experience. We need metaphors and similes because comparisons are essential in charting our way through densities of information and commentary, to make things more real and assimilable. In the US, the death toll has been compared to the loss of life on 9/11 and during the Vietnam War. At one level, the passing of this threshold in late April was offered as a point of fact, but at another, the purpose was to resonate with the horror or those events, to make a metaphor between them.

Even in “science” we see these traces. The name for the virus is itself a metaphor, taken from the appearance of the crown-like structure of the pathogen. Elsewhere, charts and graphs, indicating infection rates and deaths, have dominated presentations by the experts. But we know that however these tallies are formed, they are not the thing itself – they only approximate reality (sometimes very loosely) rather than capturing it; they constitute a representation and therefore serve a metaphorical purpose: they stand for something else.* The same is true of the models on which much government thinking and planning was based. Responding to the evidence, Governor Cuomo of New York warned in March: “The tsunami is coming.”

Throughout the crisis, metaphor has been hard at work.

*For a related theoretical argument, see Barbara Tversky, “Spatial Schemas in Depictions”, in Spatial Schemas and Abstract Thought, ed. Merideth Gattis (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2001). 79–112.