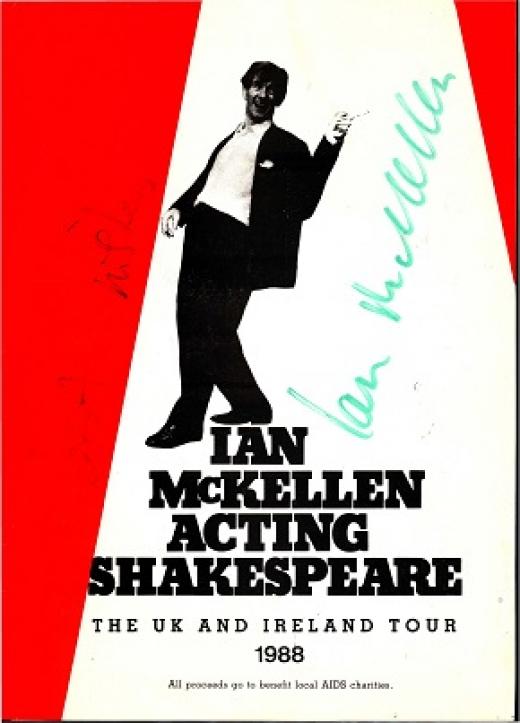

In May 1988, the actor Ian McKellen brought his one-man play, Acting Shakespeare, to Dublin as part of a UK and Ireland tour as a fundraiser for local AIDS charities. Initially performed at the National Theatre in London, McKellen packed the Abbey Theatre in Dublin for two sell-out and rapturously received performances of his miscellany of Shakespearean shorts and excerpts. The Abbey production was initiated by a teacher at Sutton Park School, Sharon Hogan, who after seeing the play in London and with a group of students, led fundraising to make the production happen in Dublin. McKellen performing Shakespeare at the Abbey raised £30,000 for Irish AIDS charities.

Looking at the depiction of illness, contagion, and disease in modern Irish drama allows us to reflect on how and when virus outbreaks and pandemics have been previously considered within society. It also allows us to consider the experiences of those who were ill or considered infected and their subsequent treatment by others, which may have resulted in stigma and social isolation. A study of the performance of viral illness is also to study social empathy, medical awareness and the impact of stigma in Ireland. But do we always empathise with those who are made ill? Or are we fearful of those who are contagious? From ‘herd immunity’ to ‘herd mentality’, there is a chequered history of the study of viral performance in Irish theatre.

Every theatre-goer who went to the Abbey Theatre, for example, over fifty years from the 1910s through to the 1960s, and who read their play programme saw the warning (or reassurance) that “In the interest of public health the theatre is disinfected with Jeyes Fluid and sprayed with Jeyes floral spray.” In decades where Dublin recorded some of the highest poverty levels and large-scale slum inhabitants internationally, as well through later decades of T.B. outbreaks, there was obviously a need, if even to just psychologically reassure patrons, the theatre was clean and sanitised.

The examination of the effects of viruses and pandemics on stage are inherently physical acts. They must represent the rapid (or at times prolonged) degradation of the body, and sometimes the mind, before an audience. In DruidShakespeare, the staging of Shakespeare’s epic Henriad cycle and directed by Garry Hynes in 2015, Dearbhle Crotty portrayed Henry IV and charted his trajectory from taking the throne and with an androgynous masculinity. Henry soon succumbed to a blotchy and menacing skin rash that visibly spreads and creeps from upon the neck, from one play to the next, soon covering Crotty’s body and ultimately sealing Henry’s fate. Under Garry Hynes’ direction, Crotty’s monarch distorts the position of gender in power, but yet whose bodily demise from disease reminds us all of our vulnerability.

Stigma is also present as a trope within many plays that deal with illness as a theme. From the 1980s onwards, in particular, those who developed HIV/AIDS in Ireland were dehumanised and separated from others and from family and social circles - a double effect of the illness that ensured physical and emotional isolation as well as the physical medical effects. As Cormac O’Brien has written, “When one examines Irish cultural responses to HIV/ AIDS in literature, drama, film, television and media - and, of course, politics - this nation's epidemic of signifiers has stigma as its common denominator.”

Recent research by Hannah Tiernan on the history of LGBT theatre at Project Arts Centre, finds works like The Normal Heart, by Larry Kramer. First produced in New York in 1985, “the play tells the story of AIDS activist Ned Weeks and his struggle to raise awareness of the disease, fighting government bureaucracy and social stigma.” It is said to be the first play that challenged the experience of AIDS in Ireland in 1987.

Eithne McGuinness was an actor and playwright from Dublin. A graduate of Trinity College Dublin, her best known play Typhoid Mary, first produced at the Dublin Fringe Festival in 1997 and later produced by RTÉ Radio and shortlisted for the PJ O'Connor award. The play tells the story of Mary Mallon, an emigre from Cookstown in Co. Tyrone, who arrived in the U.S. in the early 1880s and who by the early years of the twentieth century was one of the most notorious women in America. Working as a cook for wealthy New York families, cases of typhoid emerged and followed Mary’s reputation. Identified and feared as a ‘superspreader’ of the disease, Mallon faced numerous stints in forced quarantine and medical prisons before she died in 1938.

While a number of typhoid deaths are attributed to Mallon, the exact figure is still unknown owing to many aliases she adopted. McGuinness’ play is set in the years 1883 and 1935 and takes place within the mind of Mary as she attempts to break up the monotony of her quarantine (and imprisonment) by recalling her life story. The play carries warnings and commentaries upon the rights of those who may be asymptomatic but still actively infectious in terms of disease or virus transmission.

Enforced detainment of those unwilling to comply with policies and public advice on isolation is at times a resort in times of pandemics or mass-viral outbreaks, but it does also require the close monitoring of individual rights for individuals affected. Mallon always denied the charges against her and protested her detainment (which lasted nearly thirty years) as well as attempts to enforce surgery to remove her gallbladder, the site then thought to be the host of typhoid bacteria. In her play, McGuinness captured the nuances of medical social protection and contrasted the necessity to protect the public with the need also to tell Mallon’s perspective.

*See : “Pom Boyd in This Beach. Brokentalkers Theatre Company, 2016.”

The stigma of bodily infection was politicised by Donal Trump in his opening presidential campaign speeches of 2016, outlining his plans to build the wall to prevent migrants from Mexico he depicted as criminals and rapists. Speaking in June 2018, President Trump likened immigrants to an ‘invasion’ which would ‘infest’ the United States. Pre-empting the theme of Trump’s speech was the production of This Beach by Brokentalkers at Project Arts Centre in 2016.

Written and directed by Gary Keegan and Feidlim Cannon, the play explores the public perception of migrants as a physical plague which, to use Trump’s words, ‘infest’ otherwise pristine lands and cities (or beaches), forming a biohazard risk against humanity itself. Most tragically of all, was the image that went ‘viral’ of a rescue worker holding the limp body of a child migrant, six-year old Alan Kurdi, a Syrian boy who died crossing the Mediterranean in 2015, creating tragic links between the play and perceptions of migrants. As Susan Sontag reminds us in her book “Regarding the Pain of Others”, to view such images of tragedy through the lens of media can desensitise the viewer to the pain they are witnessing. Sontag outlines how “Photographs that everyone recognizes are now a constituent part of what a society chooses to think about, or declares that it has chosen to think about.” The surgical mask worn by Boyd’s character in the play symbolises our own voyeurism and self-isolation against the suffering of others, for fear we too become ‘infected’.

In 2016, as the Abbey Theatre was marking the centenary of the 1916 Rising and within its programme ‘Waking the Nation’, it famously became engulfed in a major social movement, ‘Waking the Feminists’ in response to a lack of work written or directed by women artists, theatre-makers and writers. Seeing The Plough and the Stars programmed in 2016 was a surprise to no one. However, it did show perhaps Ireland’s most widely known ‘viral character’ in interesting new ways. Mollser is the consumptive young girl (first played by Kate Curling in 1926) in Sean O’Casey’s play, and whose death symbolises much of the needless death caused by poor health care and lack of sanitation in Dublin’s overcrowded tenements.

Often portrayed on stage as a meek girl in a pale nightdress, a near invisible presence on the play’s impact, in Sean Holme’s direction in 2016, Mollser is instead dressed in a Manchester United jersey, skirt and Adidas runners. As the play opens, Mollser sings Amhrán na bhFiann before breaking down in a bloody coughing fit, and spits blood onto what could be the Proclamation, as a tower on stage collapses and Mollser dances to a techno dance track. The scene was a strong statement as tower cranes all over Celtic Tiger Ireland froze to a standstill in 2008. As the recent book, Recalling the Celtic Tiger edited by Eamon Maher, Eugene O'Brien, Brian Lucey reminds us, the physical as well as moral health of the nation also suffered through the contagion of Celtic Tiger excesses.

The depiction of illness, viruses and contagion in Irish theatre go far beyond these examples. They do however, show how at times class, power, authority, empathy and faith can affect how we as a society interpret these works and respond to the illnesses they portray. We are a community as well as an audience and how we treat others who seek healing or those who are isolated or stigmatised through illness reflects how we function as a society beyond the theatres.